The Magazine of The University of Montana

Animal House

From Emperor Penguins to Zebras to Honey Badgers, UM’s Zoological Museum Has It All

story by Chad Dundas photos by by Todd Goodrich

Fig. 1: Feathers of a peacock inside the UMZM's cold room

The cabinet is five feet tall, four feet wide, and so heavy that workers had to use a crane to get it up here while the building was still under construction, Dyer says. The skulls on top belong to large marine mammals—dolphins, walruses, and, the biggest of all, a pilot whale—but the real oddities are inside.

“This is probably the only place in Montana where you can see a penguin,” Dyer says with a chuckle, as he pulls off the cabinet’s bulky door and slides open one of its many shallow drawers.

Sure enough, there they are.

The drawer is full of stuffed penguins, maybe a dozen of them lying side-by-side with their bulbous white bellies thrust into the air, dark wings in various shades of fading black and gray folded at their sides. Dyer points out the biggest of the group, the emperor penguin, lying in the middle.

“This is probably one of our more unique specimens,” he says. “I’m always amazed when I look through here at the number of specimens we have. We have polar bear skulls. We have endangered black-footed ferrets. …This is the largest collection of its type in the state, by far.”

The room where Dyer stands houses the bird and mammal wing of UM’s Philip L. Wright Zoological Museum. Established by biologist Morton J. Elrod in the late 1890s and named for the professor who took over its care in 1939, the museum has been in continuous operation on campus for almost 115 years. It is fully accredited by the American Society of Mammalogists. With a collection that now boasts more than 24,000 specimens, including some 14,000 mammals, 7,000 birds, and 3,000 fish, it’s one of the major zoological collections representing the Northern Rocky Mountains.

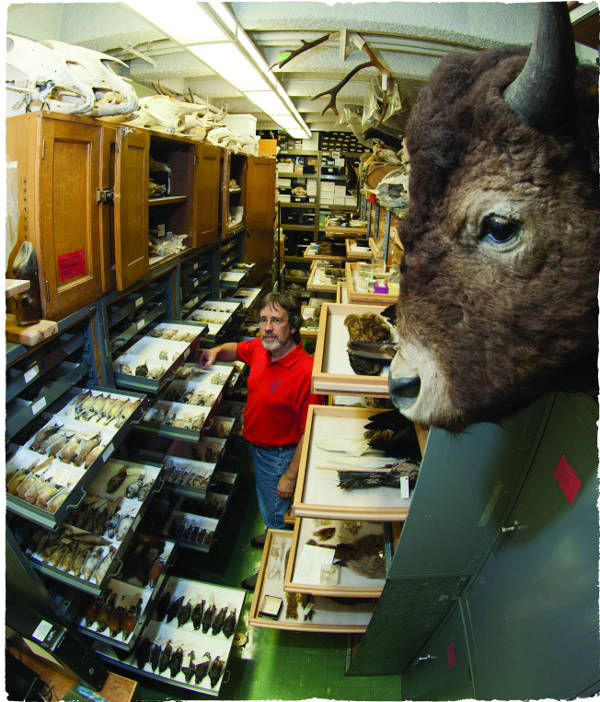

Fig. 2: Curator Dave Dyer among some of the more than 24,000 specimens packed inside the UMZM

Dyer, the museum’s affable and soft-spoken curator, a small volunteer staff, and students oversee the facility. It serves a variety of functions at UM, such as preserving specimens of both endangered and common species, hosting touring school groups, and providing specimens for scientific research while also making them available to departments on campus for teaching purposes. Frequently, museum staffers help anthropologists identify bones from archeological sites, and occasionally they do the same for the state crime lab.

“We’ve had people do their entire thesis research using this collection,” Dyer says. “There’s almost an infinite number of uses for it. Just yesterday we had some researchers come in from the anthropology department. They had some feathers from arrow shafts, and they wanted to identify what kind of birds they came from. So we were able to go through the collection and narrow it down.”

The museum’s usefulness ranges from the very studious—providing samples for DNA research, for example—to things that are far more, well, pedestrian.

“We’ve had people come in and ask, ‘Do you have a honey badger?’” Dyer says, referring to the ferocious mammal made famous by one of the Internet’s most popular memes. “We looked and, sure enough, we’ve got one.”

| “ | By all rights, the zoological museum should probably be one of the jewels of the University’s science programs and one of the school’s most popular attractions overall. | ” |

The mammal and bird room is crowded from floor to ceiling with various cabinets, shelves, and cases stocked to the point of overflow. Many of the specimens (some of which date back to the mid-1800s) are species native to Montana, but some are from as far away as Russia and China. The cabinet that houses the penguins also has drawers full of pelicans, both white and brown, and even the wilted, day-glow grandeur of a few pink flamingos. The adjacent wall is filled with bear skulls—grizzlies, black bears, Alaskan brown bears, even polar bears—and nearby are the big cats: lynx, bobcats, and mountain lions, as well as exotic specimens from Central and South America.

There are hyenas. Weasels. Porcupines. Asian and African water buffalo. Drawers full of primates. Drawers full of vampire bats. Endangered species such as sea otters and black-footed ferrets that have to be stored alongside special federal permits. There is a jerboa, a hopping desert rodent native to northern Africa and parts of Asia that has the body of a mouse and legs like a tiny kangaroo. There is even a Russian desman, a rare aquatic mole whose distinctive feature is a wide, flat tail built for swimming.

“A researcher saw this in our collection, and he was shocked that we had it,” Dyer says of the desman. “He said it is maybe in only three museums in North America, and we have one. That’s probably the most unusual thing that we have. Anybody studying mammals I think would be excited to see something like that. You’re not going to see it anywhere else.”

Fig. 3: Many of the specimens are stored in glass jars.

Next door is the museum’s skull room and beyond that the refrigerated cold room, where you’ll find the skins of more bears, wolves, and lions, as well as sloths, anteaters, and even a couple of leopard skin rugs made in India during the 1950s.

The sheer number of specimens staggers the imagination. By all rights, the zoological museum should probably be one of the jewels of the University’s science programs and one of the school’s most popular attractions overall.

There are just a couple of problems.

The museum doesn’t have the space or the funding to be set up to adequately receive the public. Most of its specimens, such as the penguins, are stored in cabinets and used primarily for teaching and research purposes. As a result, few people know this place or the collection itself even exist.

Emily Graslie spent last week hauling animal hides out of the cold room after the refrigeration system sprang a leak. Until UM’s Facility Services department can get it fixed, Graslie needs to locate a different place to store some of the museum’s large animal skins before they suffer any more damage.

“I’ve got a zebra that’s falling apart,” she laments.

Graslie studied art at UM but significantly altered her life’s path after a co-worker at the UC Market introduced her to the wonders of the Wright museum. Now a full-time volunteer curatorial assistant at the collection, she works five days a week helping Dyer keep the museum up and running. It can be a taxing and sometimes frustrating job. The collection outgrew its cramped space in the Health Sciences Building long ago, and after operating for more than a century on what pretty much everyone involved admits is a tight budget, problems are beginning to crop up. Unfortunately, the leak in the cooling system seems fairly typical of what the staff here goes through on a regular basis.

Many of the museum’s storage cabinets are old and in disrepair, Dyer says, and the staff is now preparing a grant proposal to the National Science Foundation to purchase new ones. The most critical need, however, is space. Because the collection consistently grows and takes on new specimens, and the museum has seen an overall reduction in the space allocated for it during the past decade, its current facility just can’t hold it all.

The museum’s collection of fish, for example, currently is unavailable, packed away in boxes and stored in the basement of another building on campus. In mid-May, numerous specimens—some of them stored in flammable alcohol—were lost when a leak caused a stack of cardboard storage boxes to collapse and several glass jars fell to the floor and burst. The police and fire departments had to be called for cleanup, and now museum staffers worry about the future of the fish collection, part of which dates back almost 100 years and represents the first reported cases of certain species in Montana.

“It’s been quite a problem,” Dyer says. “We’re pushing the administration to try to get more space to store them here. Some of these are really historic specimens that need to be saved.”

Fig. 4: Curatorial assistant Emily Graslie has volunteered thousands of hours working in the UMZM.

Space and funding also are the major impediments to the museum staff’s ultimate goal: to build a permanent, visitor-friendly natural history museum on campus. In other words, they want to get the collection out of its storage cabinets and in front of the public.

“One of my big goals is to get an actual museum built on campus, where people can come in any time of the day and see this material instead of having it all behind the scenes,” Dyer says. “That’s been a big push. The problems with that are money and staff and resources. That’s always what you come up against.”

Graslie, who estimates she’s already donated some 2,300 hours of volunteer time to the museum, agrees.

“I think that is the ultimate goal for the museum,” she says. “The alternative is that we don’t get any more space and this stuff is going to go into storage and be forgotten for fifty years, and fifty years from now we’ll be right back to where we are today.”

Museum staffers have undertaken some outreach and fundraising efforts recently, including a drive by Graslie to increase the collection’s online presence. For now, they also are settling for creating small exhibit cases in different buildings on campus, like in the Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library and on the ground floor of the Health Sciences Building.

Someday soon though, Dyer and Graslie hope more people will be able to see the penguins.

And the honey badger.

And the leopard skins.

And everything else.

“You tell someone you have a natural history museum on your campus, and that is the first thing that people want to go to,” Graslie says. “If the University gave us space, I would work day and night to make it a beautiful exhibit space. I’m so passionate about this. It’s all I want to do with my life. I want to take these things off these crowded shelves and put them in a place where we can share them with other people.”

Follow the UMZM Online

Since she began volunteering at UM’s Phillip L. Wright Zoological Museum, one of Emily Graslie’s tasks has been to bring the 100-year-old collection into the twenty-first century.

So far, so good.

Last fall, Graslie—an avid painter who graduated from UM with an art degree—started updating the daily goings on at the museum on Tumblr, a popular photo-based blog site. She uses the blog to post pictures and videos of the collection’s more interesting specimens, to keep the public abreast of the collection’s struggles (the cold room leak and the “fish collapse” are both documented), and to occasionally seek donations.

“There is a lot of potential for photographing [these] visually appealing things,” she says. “The stuff in jars and all kinds of things that I’m sure people would love to see as much I love looking at them.”

The response has been positive. After she’d been running the site for less than six months, Tumblr picked up the blog as one of its “featured spotlights,” giving it a link from its well-trafficked front page.

The blog’s features also include Graslie’s recurring “Freak of the Week” posts, where she publishes pictures of one of the museum’s more interesting or obscure specimens and challenges readers to correctly identify it.

The UMZM’s Tumblr site may not be for the weak of stomach (it comes with the disclaimer that “images on the site may be graphic or contain graphic elements”) but for those interested in keeping tabs on the museum’s operations, it’s a can’t miss.

On the Web:

The Philip L. Wright Zoology Museum’s official website:

http://zoologicalmuseum.dbs.umt.edu/.

The collection on Tumblr: http://umzoology.tumblr.com/.

Email Article

Email Article